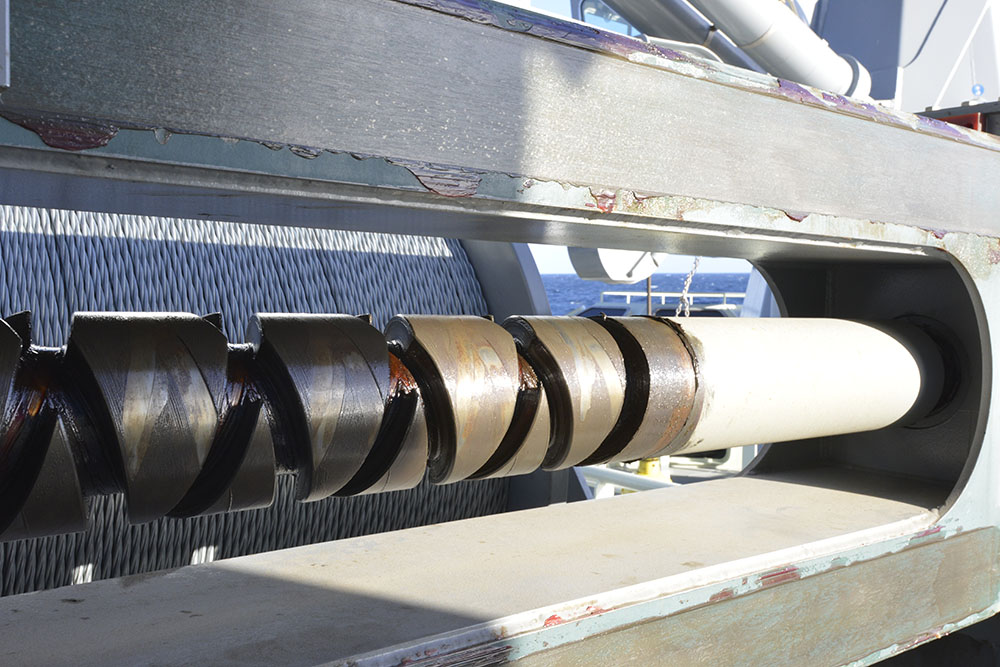

Things get busy anytime Neil Armstrong returns to port, but when there’s just a little over 24 hours to completely unload and reload a packed ship, well, things get downright hectic. Fortunately, there’s a method to the madness.

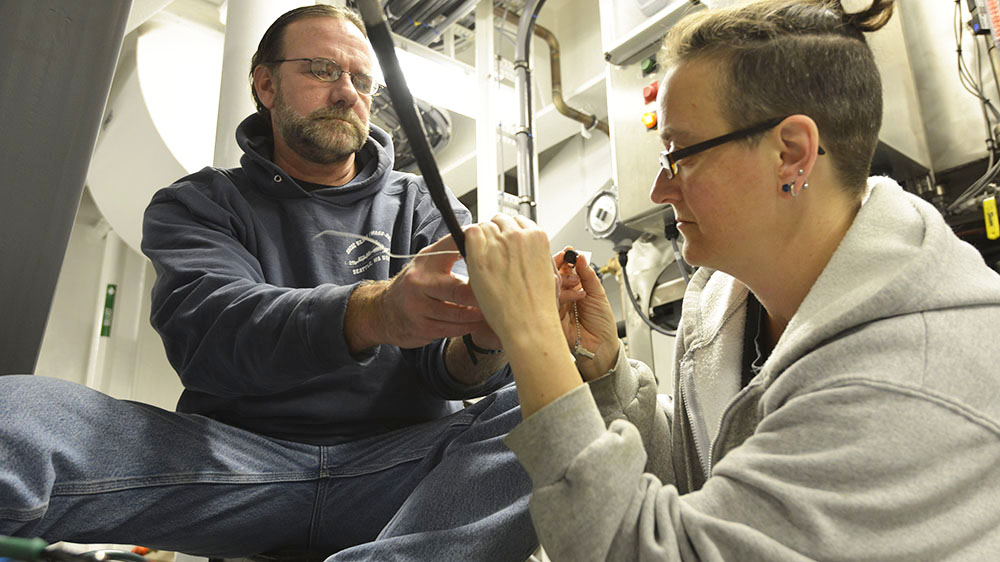

When the ship came back from leg 2 of the Fall 2017 Pioneer Cruise, it was carrying two large Coastal Surface Moorings and all the associated instruments, vehicles, and equipment—and then the crew had to load roughly an equal amount of gear associated with six Coastal Profiler Moorings. The mooring technicians, dock crew, and ship’s crew all worked from a master plan formed from years of experience, and made it all look easy.