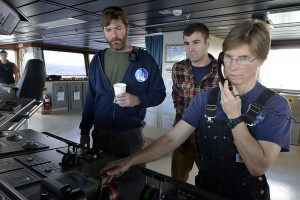

Captain Kent Sheasley, relief chief mate Derek Bergeron, and second mate Jen Hickey (left to right) learn the ins and outs of their new ship so more scientists can get out on the ocean. (Photo by Ken Kostel, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

Building a ship like Neil Armstrong and its sister ship Sally Ride is not cheap, but compared to what they will give us over the next 40 or 50 years in terms of knowledge about the ocean, they will almost certainly pay for themselves many times over.

The ocean sustains us. It makes Earth livable and makes life as we know it possible. It harbors the greatest diversity and abundance of life on our planet and it is the single largest living space that we know of. Anywhere. Oceans on one of the moons of Jupiter or Saturn may eventually prove to be larger or richer and more biodiverse, but right now the ocean that covers more than two-thirds of Earth is the only one we know of in the solar system—and it is the one that defines our planet and our existence.

When you look out over the oce an, that unbroken horizon and the relative sameness of that surface hide a complex world that borders on the fanciful. The seafloor is a vast terrain more spectacular than almost anything on dry land. There are peaks higher than Everest, mountain ranges longer and more rugged than the Andes, fissures deeper and more awe-inspiring than the Grand Canyon, and plains that could swallow the Sahara.

an, that unbroken horizon and the relative sameness of that surface hide a complex world that borders on the fanciful. The seafloor is a vast terrain more spectacular than almost anything on dry land. There are peaks higher than Everest, mountain ranges longer and more rugged than the Andes, fissures deeper and more awe-inspiring than the Grand Canyon, and plains that could swallow the Sahara.

But in many respects those are tourist attractions (with a nod to the geophysicists and the forces that created the topography.) The ocean is also teeming with life, from shallow coral reefs to the sediments beneath the deepest trenches. Some of it provides us with food, and for nearly one billion people on the planet – many of whom live in developing countries – seafood is a primary source of their daily protein. Smaller and less charismatic organisms, marine algae, produce as much or more oxygen than all of the forests on land combined. Think of them the next time you take a breath. Marine microbes, many of which have yet to be named or understood and some of which hold the potential for novel materials or life-saving drugs, are more abundant than stars in the known universe.

And yet, for all its importance to us and to every other living thing we know of and to almost every planetary system that helps make Earth livable, we know remarkably little about what goes on at or beneath the ocean surface, let alone how human activity is beginning to alter the way it works. That’s not to say that we don’t know anything. In fact, we know quite a lot, which is a testament to what can happen when curious, motivated scientists and engineers have the opportunity to go to sea. But research ships are scarce and ship time for scientists woefully short to fill the gap between what we know and what we need to know. And that gap only seems to widen every time we learn something new.

One thing that has become abundantly clear in recent years is that the ocean is changing. Humans have long seen the ocean as virtually limitless and untouchable and so have used it as a dumping ground for waste and refuse. The impacts that resulted were relatively confined, but now the changes we see span the globe and echo throughout the water column. Surface water is getting warmer as a direct result of humans burning more fossil fuels and pumping more heat-trapping carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. As a result, individual species and entire ecosystems are rearranging themselves, not always successfully. Precipitation patterns and other elements of the climate that dictated how and where humans settled on land are also reshuffling in response to the physical changes we’re forcing on the ocean. And now the ocean’s very chemistry is also changing, growing more acidic, again as a direct result of the increase in carbon dioxide in the atmosphere and with any number of potential impacts on marine ecosystems—none of them good.

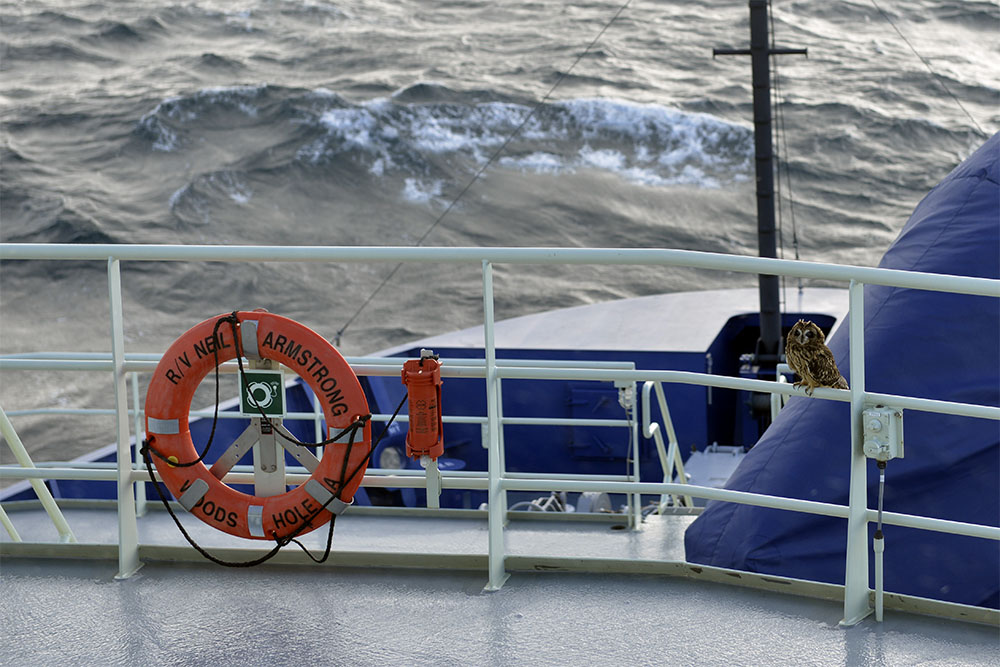

To study the ocean—to understand how it works, how we are changing it, and how those changes are likely to affect us in turn—we need ships like Armstrong and people to go to sea on them. We need to put our instruments in the water, take samples, make measurements, and to do it all again next year. Or next season. Or tomorrow.

That is why we build ships like this one. And why we need more of them.